A Walk in the Park with Buildings and Food

In conversation with an electronic artist from Canada whose jaunts in the backcountry help shape her musical identity

Welcome to Instrumental Conversations, an interview series with artists, label owners, and other creatives in the ambient and instrumental music space.

In this second issue, I spoke to electronic artist

(AKA Buildings and Food) about her new record, Provincial Park, which was released independently on May 9, 2025.I often think how unnatural a connection it should be between electronic music and the natural world. And yet, these two entities seem to be inextricably linked. Opposite identities that can only exist because the other does too.

Mort Garson’s Mother Earth’s Plantasia. Hiroshi Yoshimura’s GREEN. Gas’s Pop. These are just a few examples of remarkable electronic albums that captured the sentiment of organic life through the manufactured sounds of synthesizers and field recordings. It’s difficult to determine precisely how the digital oscillations of machines can so obviously represent the diverse array of earth’s biomes and organisms. As I often find myself resolved to thinking when considering the abstraction of ambient and electronic music: it’s just another one of those things you know when you hear it.

It brings me great joy knowing that there are artists out there like Buildings and Food who continue to explore our natural world—a world that is currently in undeniable crisis—and take inspiration to create new electronic works that transcend the boundary between woman and machine, between the biological and the mechanical.

Buildings and Food is the independent electronic project of multidisciplinary Canadian artist Jen K. Wilson, who has released music under the Talking Heads-inspired moniker since 2018. Wilson is a classically trained pianist and self-taught multi-instrumentalist who also dabbles in visual art.

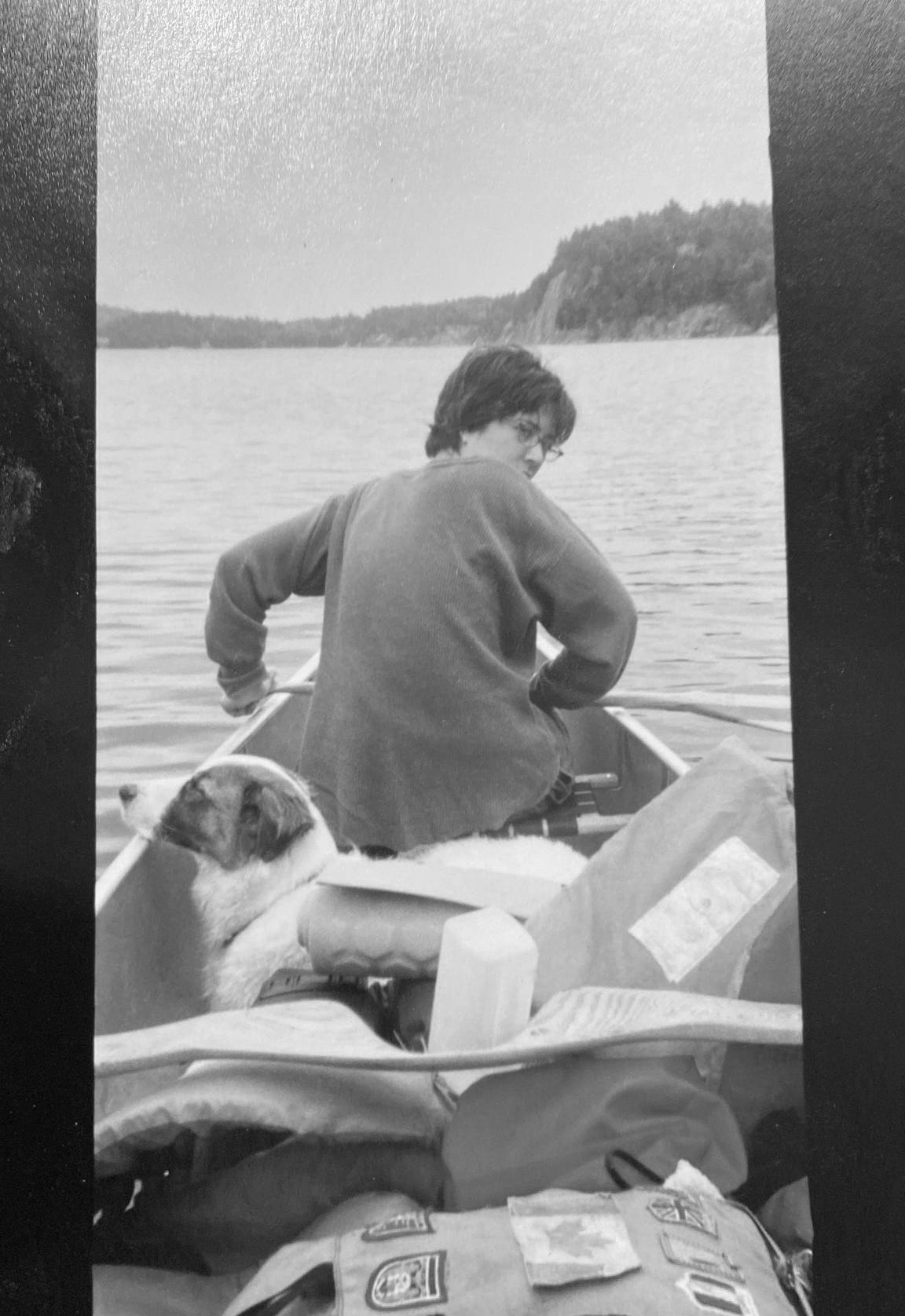

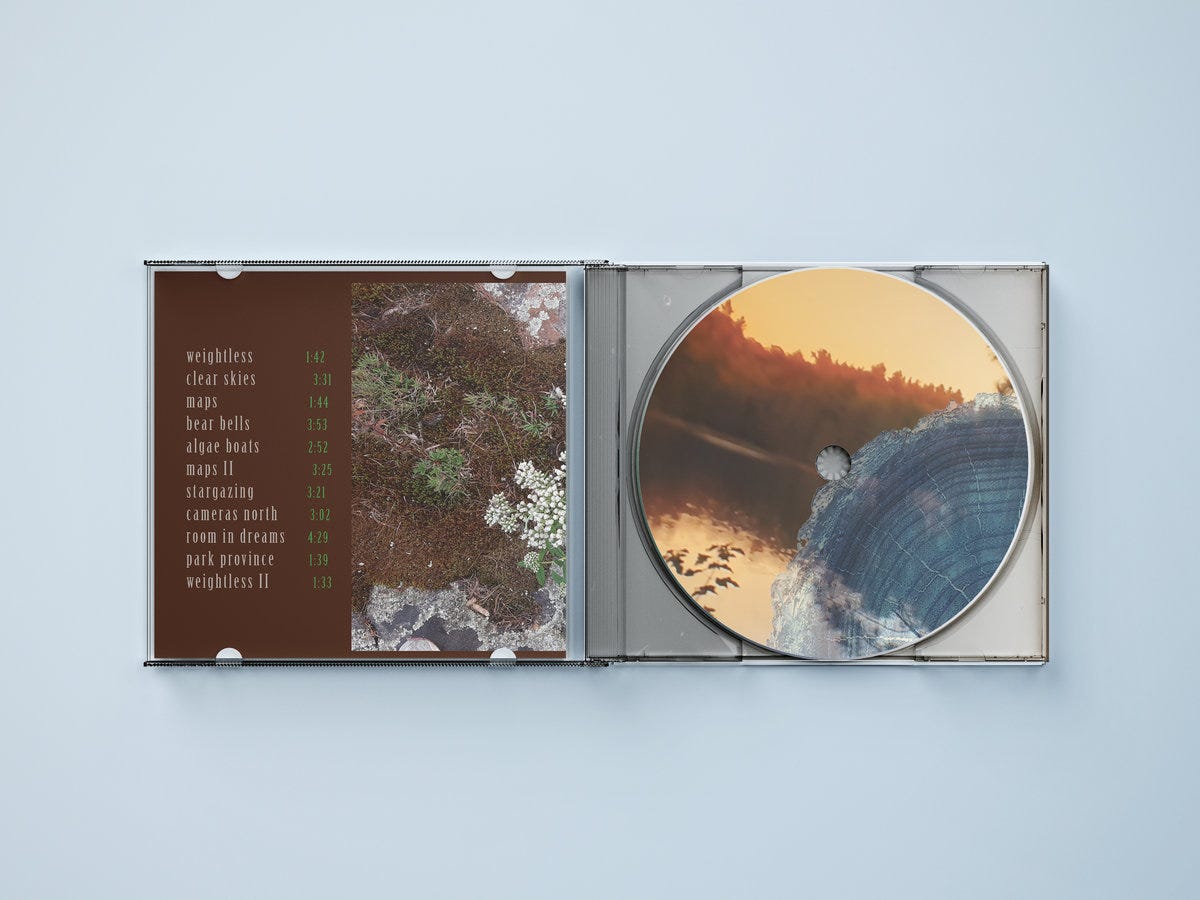

On May 9, Wilson released Provincial Park, her fifth full-length album as Buildings and Food. The melodic ambient LP, named after the many parks administered by Canada’s individual provinces, is a reflection of Wilson’s outdoor encounters with Canada’s backcountry, where she spends countless hours canoeing, hiking, and meditating in the serene quiet away from the bustle of urban centers.

Like the many nature-inspired electronic albums that preceded Provincial Park, Wilson’s new album does not feel concocted or prearranged—there’s an essence of nature’s ongoing renewal in this record’s DNA. Whether its the subtle details of the percussive textures that jitter behind the looping melodies on tracks like Weightless and Clear Skies or the unadulterated field recordings of Park Province, there are always new signs of life emerging within Provincial Park.

Read on for my full conversation with Jen K. Wilson about the record, her inspirations, her production process, and the reasons she feels drawn to instrumental music:

Melted Form (MF): What emotions, events, and experiences led you to create Provincial Park?

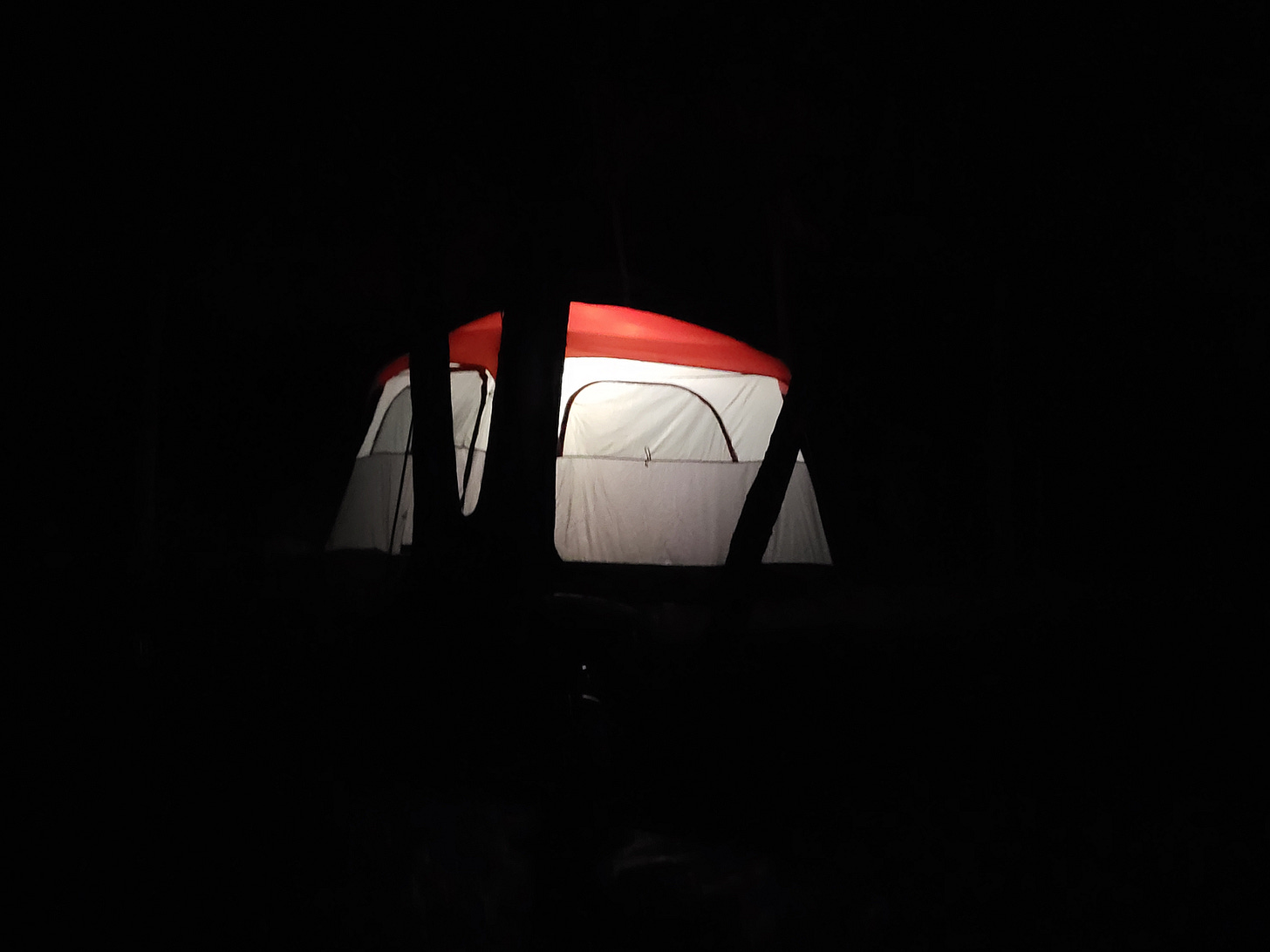

Jen K. Wilson (JKW): I travel through the backcountry in national and provincial parks in Canada regularly and have an awe-inspiring experience every single time. Connecting with nature is such a therapeutic activity; besides the fact that I simply enjoy it, its benefits are far reaching. With this release, I wanted to contribute a small part in raising awareness about the beauty and importance of nature, encouraging us to reflect on our role in protecting it. The current state of the world can be so discouraging, where the bottom line, and both government and business oligarchs, ignore the climate crisis and actually aim to make things worse rather than better. This theme of celebrating a small piece of nature evolved naturally from my concern for the environment and my great experiences in the wilderness: sleeping outside among the animals, climbing mountains, enjoying wildlife encounters, canoeing through amazing landscapes, and studying the minutiae of lake life, to name a few. I gather inspiration from all those things when immersing myself in these environments and I thought it was time I acknowledged this big part of my life through music.

MF: How have your feelings about the sound of the album evolved from the beginning stages of creation until now? What does Provincial Park mean to you?

JKW: For me, when a project is in the early stages of creation, there is always a lot of room for experimentation and a long period of sound exploration. I love creating new synth sounds and trying out the same chords with different sounds to compare the moods created. Very often a great sound will be a springboard to creating a series of pieces because I'll be inspired to follow that particular tone or mood and the sound alone can conjure up associations with certain memories or feelings. In contrast to this method, I'll write chord progressions on the acoustic piano and then play around with them in the studio with my synths to see how the piece translates to an electronic sound. As I was working on this project, memories and images from different experiences began to take hold and the album started to come together. To me, Provincial Park is a symbol of tranquility and wonder, an escape or therapeutic place to be. I like to think that the album can offer the listener a refuge, a peaceful bit of time/space to experience as you navigate your hectic, stressful day. It certainly was that for me, while creating it. I've previously described the album as a love letter to the Canadian wilderness and that's really what it feels like it to me. I'm very grateful for the time that I am able to spend there and truly appreciate all that it provides.

MF: I know there are themes of nature's many wonders in the album—what fascinates you most about the specific ecosystem of living things from which you drew inspiration, and how did that translate into music? How does your relationship with the Canadian landscape shape your identity as an artist?

JKW: It's amazing what you can see and experience, when you slow down and study the smallest spaces. You can be in one spot for a couple of hours and just drink in the plethora of sights and sounds in the space around you when immersed in the wilderness. The tiny amphibians, insects, and fish, as well as the larger land animals (bears, beavers, wolves, moose, caribou, deer, coyotes, herons, turtles, eagles, owls and loons, snakes, frogs and toads, grouse, turkeys, I could go on, lol.) I have a bit of a fear of bears when in the wilderness, which is why I carry bear bells when hiking. There is always the hope that you'll see a bear but at the same time you're hoping you don't. Then of course, escaping the concrete to be surrounded by a haven of trees is an amazing thing. My love of the Canadian wilderness and landscape does so much to shape my artistic identity. It encourages reflection and contemplation, allowing me to explore my own place in the world and express myself. It informs my personal narrative through my experiences and memories and helps me create a story that reflects my identity. I'm also a visual artist and have a really visual relationship with music. Melodies and patterns create visualizations for me and I often express something musically based on the visualization of something. I'd say the music on this album is a form of abstract expressionism, drawing inspiration from the natural world and interpreting it and my relationship with it. There is also some symbolism there, notably with Weightless and Weightless II, which open and close the album.

MF: Do you have a favorite track on the album, and if so, why?

JKW: Maybe Algae Boats... I think it captures the calm of canoeing on a still lake. Maybe Maps.... I'm a sucker for a waltz and I find it really dreamy.

MF: Who are your greatest musical inspirations and why?

JKW: I am inspired by so many forms and genres of music and it's always evolving. It's really impossible to list my greatest inspirations overall because the list of musicians is so vast. I can say that in terms of ambient music, Hiroshi Yoshimura is one of my favourite artists, as well as Susumu Yokota, Boards of Canada, and Dntel.

MF: Tell me more about "Buildings and Food"--did the name come from Talking Heads? What does it mean to you?

JKW: Yes, I took the name from the Talking Heads album, More Songs about Buildings and Food. When I was first trying to come up with a name I had no idea how my music would evolve over the years and I'm not sure how the name fits with the music I make now, but with my first album, the music was still coming from a pop sensibility. At the time, I was reminiscing about the impact that the album had on me when I first heard it. It was the first Talking Heads album that was produced by Brian Eno, whom I was already a big fan of, and I loved what his involvement contributed to the album. The name also created an association for me, of music being an essential part of life, like water, community, books, or buildings, and food! But really, "What's in a name?”

MF: Reflect on your work up until this point--what were your earliest musical experiences like and what are some lessons you feel like you've learned throughout your career as an artist?

JKW: I studied classical piano throughout my childhood and youth and taught myself guitar, clarinet, cello and drums, so I was really fostering a deep relationship with my instruments, while being exposed to all sorts of music, from classical, obscure jazz and blues to different forms of popular and world music. I've been writing music since I was a kid and those early songs were informed by whatever music I was listening to at the time. In my youth and as a 20-something, I was really trying to emulate music I loved but in my own way. It was challenging to avoid sounding derivative. By the time I released my first solo album, I had let go of that objective of trying to sound like someone else and I really think I found an originality in my music. Rather than focussing on emulating a particular sound, I was much more focussed on the writing and let my influences seep in peripherally. Over the years, I've also learned that allowing lots of room for experimentation and chance versus design can result in all sorts of happy accidents and new discoveries.

MF: Is there anything you'd like to share about your production process that other independent electronic/ambient artists might be interested to know? Feel free to touch on gear, software, techniques, etc. Were there any pieces of gear that played a major role in the creation of Provincial Park?

JKW: I have a pretty basic studio set up with a few synths, an acoustic upright piano and a mini modular synth. I have other acoustic instruments lying around but for Provincial Park I just used the aforementioned instruments and an electric guitar. All of the percussion and drum tracks were acoustic or hand played on my midi keyboard through Cubase. I mostly approached this album from a music production standpoint rather than from a traditional songwriting one. Although a couple of pieces were written on the piano, most of the tracks had beginnings in improvised sessions and sample creation, and there was a lot of experimentation with sounds and manipulation of recorded material with signal processing. Running synth sounds through an old tape recorder to align them with the aged quality of the field recordings I had was a fun way to distort clean sounds, rather than using tape plugins. I do love the ease of plugins but sometimes you just want to get your hands dirty and use machinery.

MF: Ambient music has often been described as both background and foreground—music you can ignore but also get lost in. Where do you see Provincial Park on that spectrum?

JKW: Provincial Park has elements of both, I think. Some of the tracks are definitely meditative and lean towards drone or soundscape, but others are more compositional. For the most part, I'm interested in creating ambient music that requires a more active role for the listener. I think it's just in my nature to be inclined towards writing melody and counterpoint and I really have to hold myself back a bit when making this type of music. With this album, I wanted to encourage contemplation, and create a sense of peace without necessarily making you want to fall asleep or put you in a trance.

MF: Lastly: What draws you to ambient/instrumental music? (can answer in the context of listening and/or creating)

JKW: I am mostly drawn to instrumental music due to the fact that, as you mentioned earlier, it has the ability to exist on multiple planes; it can exist as purely background ambience or be fully immersive, there for the listener to pay close attention to. Instrumental music in general has this quality that allows the listener to develop his/her/their own interpretations and emotional connections with the music. As far as creating the music goes, the process of writing and producing this genre is a blast and a balm. Like looking inwards or outwards, through a microscope or a telescope, anything seems possible.

Provincial Park is available for purchase and listening now on Bandcamp. You can buy it on digital or CD.

Thank you for reading, friend. Until next time.

Your friend,

Melted Form

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Jen K. Wilson for participating in this interview and sharing her thoughts and music with me.

Want more great ambient music? Subscribe!

Every Friday, I send out a newsletter with new music recommendations, including a handful of great new ambient records. I prioritize small label and indepedent artists, but I also share a list of major records I’ll be listening to from other genres like electronic, indie, alternative, jazz, pop, and more.

Read my latest weekly post:

Read the last issue of Instrumental Conversations:

Thank you Melted Form!