Finding Consolation in Resonance with Poulson Sq.

In conversation with the duo about their recent collaboration, 'Battles and Silences'

Welcome to Instrumental Conversations, an interview series with artists, label owners, and other creatives in the ambient and instrumental music space.

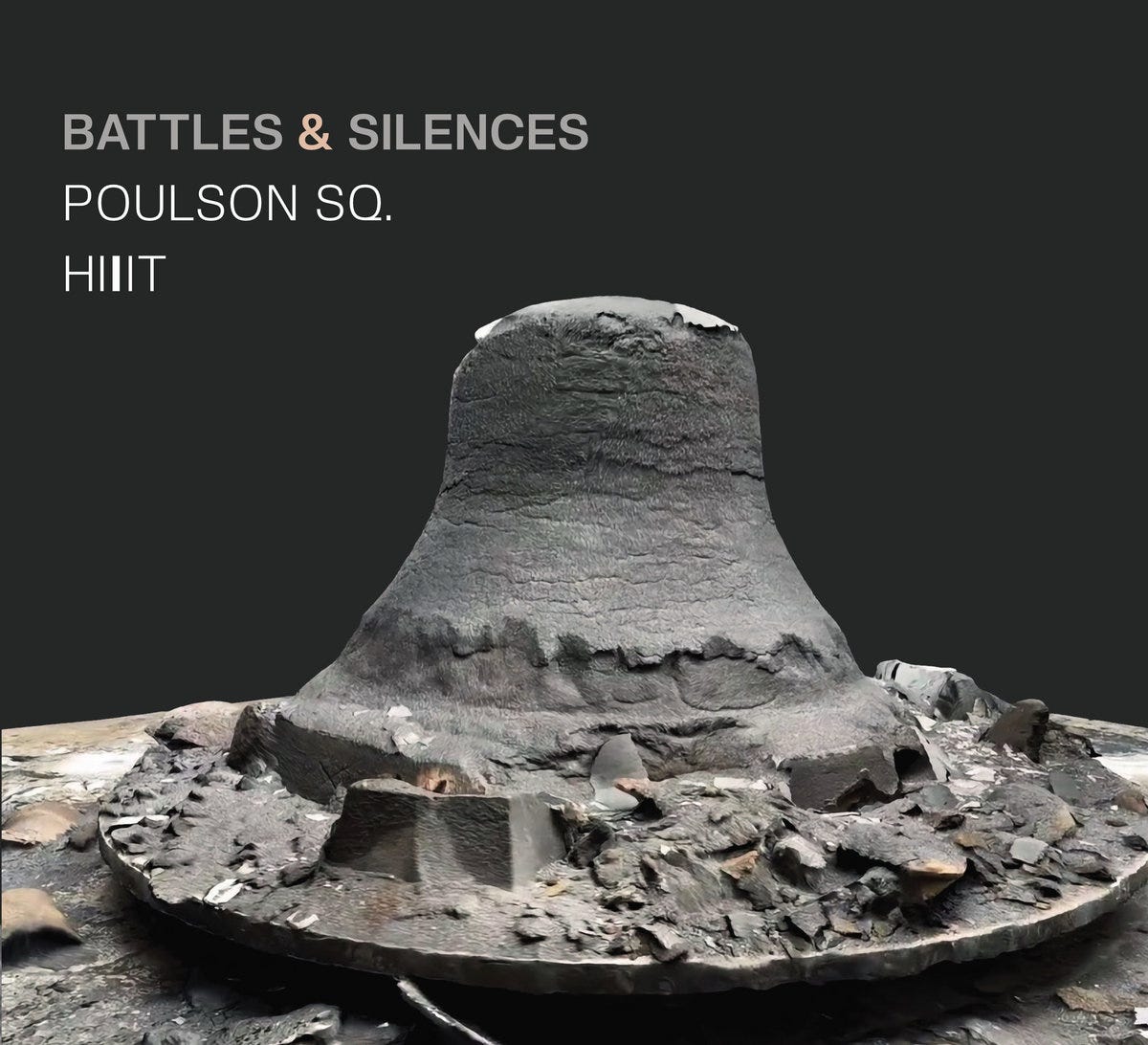

In this fifth issue, I spoke to experimental electronic duo Poulson Sq. about their album, Battles & Silences, which was released on November 2, 2025.

As these conversations run long, email readers may need to scroll down and click the button to open this in their browser/Substack app to read the full issue.

What does war sound like?

For those of us fortunate enough to have lived out of reach of direct armed conflict, we can only imagine the imitations of war we’ve witnessed in media—blockbuster action movies, harrowing video games, gripping TV series, and limited view news coverage.

Bullets crack, ping, and thud against their targets of stone, metal, flesh. Explosions trigger tinnitus reactions that ring in one’s ears like ten thousand teapots boiling over. Shouts and guttural utterances of pain, terror, and violence—all of this is the Hollywood horror we’ve heard.

But what if most of war’s reality sounds different? What if bullets began to sound different long after they were fired? What if the eerie silence—and the emotional turmoil—that follows bouts of battle sounds far more haunting than any media depiction could capture?

These are questions I began asking as soon as I encountered Battles & Silences, a collaborative work of experimental tape music composed by electronic duo Poulson Sq. (Anthony Fiumara and Mathijs Leeuwis) and performed live alongside Dirge Seçil Kuran and João Brito, members of The Hague/Amsterdam-based music collective HIIIT.

On Battles & Silences, Poulson Sq. and HIIIT have crafted sparse, ominous battlefields of noise where all that lingers is the memory of destruction.

Static and indistinct, metallic recordings clash and buzz. Dark drones loom beneath, then vanish, then reemerge to raise hairs and vibrate bones.

It’s all echoing together. Was that a rifle firing? A hammer striking something stout? The battle is close.

No, voices now—crying out, lamenting in the wake of the violence. Or is that the air moaning as a bomb slices through it during its descent?

Through all the progressions and recessions of noise, among the ashes of heavily processed samples recorded on analog tape, between the battles and the silences… I can hear a faint harmonic element. A centering, grounding sound.

A bell.

In 2024, 8 kilograms of Ukrainian bullet casings were melted down into bars in Kyiv, then shipped to the Netherlands and cast into a bell at the Royal Eijsbouts Bell Foundry. Weighing a total of 45 kilograms (just under 100 pounds), this new bell, the artists say, “heralds the beginning of a natural rotation: destruction becomes beauty once again.”

But this bell’s beauty is not detached entirely from the destruction that preceded it—it carries the weight of the battles in which its materials once flew around like hell’s hawks. It remembers. We remember. We must remember.

And we must appreciate the silence between the battles, which we often fill with melody to ease the memories that seep through in the silences. Redirect them into something like a song. Or something else...

Read on for my full interview with Anthony Fiumara and Mathijs Leeuwis of Poulson Sq. to learn more about their work and this soul-stirring record, Battles & Silences.

Meet Poulson Sq.

Please tell me more about the name Poulson Sq. Where did it come from and what does it represent about your musical identity as a duo?

Mathijs Leeuwis (ML): Valdemar Poulsen was the Danish engineer who developed the wire recorder. In current days aesthetics the wire recorder is an inferior machine. Despite all its technical shortcomings, it simultaneously contains so many artifacts that it pushes things to the fore besides the original message/information, that it triggers new associations and thoughts. Seen this way, the wire recorder forms a kind of template for how we often work as a duo: we try to give a place to the periphery of sounds, processes, instruments and sound worlds. A shift in perspective, prompted by the technical imperfection carried within our mostly analog set-up. This aspect of our compositional process feels so fundamental that we have chosen to give Poulsen, albeit slightly altered, a place in our artist name. The addition of “Sq” refers to our shared idea that we are working on pieces that try to place themselves outside of time. Not a linear story with a beginning and an end, but a sound structure in which you can dwell. A place, a square.

How long have you each been making music (both independently and as a duo)? What was one of your earliest memories of music that made you each want to become an artist?

Anthony Fiumara (AF): The short answer is that I’ve been involved with music for most of my life, though my way into it wasn’t particularly straightforward. As a child, sound fascinated me more than songs did: the hum of the refrigerator, the drone of traffic outside, the self-made electronic circuits that I connected to my stereo set, blending into something strangely consoling. Those were probably my first “musical” experiences, though I didn’t yet have the language to call them that.

Although I played in punk and new wave bands in my years in high school and early university, composers were dead people on clouds—out of reach for me as an ordinary mortal.

I started composing seriously in my early thirties, after exploring other forms of creative work. It was only then that composition began to feel like the natural way to think. Over the years, my focus shifted from notes and gestures to timbre, structure, and the physical experience of sound.

As for the duo, we began collaborating in 2020 when our shared interests in slowness, texture, analog processes and reduction revealed a common ground. Collaboration, for me, has always been a kind of conversation: you listen, you respond, and you let the space between things speak. That dialogue—between two people, or between silence and sound—is what continues to draw me to making music.

ML: Just as for Anthony, music has always been around. Mostly songwriters and classical music was what was played back home. My first profound experience with music was probably around the age of 14, when I started playing electric guitar: the loudness and recognition of the sound that referred to completely different worlds (at the time, mainly from bands like Nirvana) was a fundamental feeling. It was as if you could access another world through that instrument. From there, I started throwing parties with groups of friends, making electronic music, playing in countless bands, studying guitar. But almost everything took place outside of institutions, which meant that for a long time I felt a great distance from forms of institutionalised music. Ultimately, the question “what else can be done with sound” moved me towards a more formal musical study. Funnily enough, it was Anthony Fiumara who showed me that the experiments I was conducting for myself were part of a great tradition. I think Poulson Sq. is, in part, a practical elaboration of that idea.

Where do you live now and what drew you there?

AF: I was born in Tilburg (The Netherlands), the place where Mathijs lives and where I teach composition at the conservatory. At a certain point I moved to Amsterdam, because of my work as a music editor in a publishing house. I’ve been living there for the last decades, but I am moving to another city next year. Amsterdam is a good place to live and it is a cultural hub. But it is also a tourist trap and never silent.

ML: I was born in Waalwijk, close to Tilburg. I moved to Tilburg at some point. It is a city with some sort of a DIY mentality. You can get things done there. There is a mentality of absurdity and creativity. It is there that I run my own foundation/studio—Het Concreet—which focuses on artistic research through the use of analogue techniques. I feel supported by the local scene of musicians, composers and government.

What draws you to ambient/instrumental music? (can answer in the context of listening and/or creating)

AF: What draws me to ambient and instrumental music, both as a listener and creator, is its capacity to engage with sound in a profound and tactile way. Ambient music, in particular, offers an environment where sound can unfold slowly and spacefully, allowing the listener to inhabit a sonic atmosphere rather than following a narrative or melodic line. This aligns deeply with my artistic focus on what I call “the skin of sound,” which is about texture, timbre, and the physical presence of sound itself.

Creating ambient music lets me explore contrasts between stillness and movement, repetition and variation, crafting soundscapes that evoke emotion and thought without words. For me, it’s a way to engage with time differently—where every detail matters, and the experience is immersive. As a listener, ambient music’s openness invites reflection and a heightened awareness of place, shifting how I perceive space and sound daily. This quality makes it endlessly compelling and a rich terrain for artistic exploration.

ML: I must say I’m fairly all over the place when it comes to musicking. Nowadays I listen to noise, industrial and other types of sounds, often more on the extreme side of the spectrum. And this also reflects in my own current artistic practice. But one of the aspects which brought me here is the sense of texture or physicality in music, which is often strongly represented in ambient music. I think this relates to what Anthony describes as the skin of sound. In a lot of my musical upbringing the element of virtuosity was present as a leading principle (not that I ever come close). And I think that it was through ambient music that I got drawn to aspects as slowly unfolding timbral changes as a focal point. As such, ambient music holds an important place in my personal musical development.

What music do you typically find yourself listening to? Any favorite artists? Any records that inspired Battles & Silences or any of your other music as you were working on it?

AF: Typically, I find myself listening to a broad range of ambient, electronic and contemporary experimental music that emphasizes texture, space, and subtle transformation. Artists like Brian Eno have been influential, alongside composers like William Basinski, Steve Reich, Morton Feldman and also Iannis Xenakis, whose work explores atmosphere and the physicality of sound in different ways. These artists create immersive listening experiences that resonate strongly with my own approach to composing.

Regarding records that inspired my work, including the album Battles & Silences, the immersive slow unfolding of ambient textures and the thoughtful manipulation of silence and sound have been central. The process and the soundscapes of these artists informed how I think about space in music and the balance between presence and absence. Their work helped shape my interest in how minimalism and subtle changes can create profound emotional and spatial effects in music.

The album Sti.ll by Taylor Deupree was an inspiration for us. More process-wise than sonically. We used the idea of asking musicians to translate tapeloops, sounds and noise to their instruments. And Basinski’s disintegration of sound was also a starting point.

ML: The earlier mentioned Sti.ll by Taylor Deupree is specifically important for Battles & Silences. Mostly as a reference to approach the musicians we were working with. I noticed that it was very helpful to share this music with the people involved: a lot less words were needed to get to the point of understanding what we were going for.

Like I said: I’m listening to a lot of different things, running from noise to drone and free improv. One recurring theme in my listening is early (electronic) music. Besides my work as a composer, I also run the experimental lab space Het Concreet, which is completely built around the use of analog electronics to explore sound. As such I’m constantly researching historical techniques for the composition of electronic music. This ongoing research is also strongly reflected in the kind of music I listen to, so a lot of Bernard Parmegiani, François Bayle and the likes.

On Battles & Silences

What connection do you have to Ukraine that inspired you to take on the Battles & Silences project with HIIIT? How have your feelings about the sound of the album evolved from the beginning stages of creation until now? What does Battles & Silences mean to you?

AF: The artistic director of percussion ensemble HIIIT and I have a fascination for metal percussion and bells. The original idea to center a performance around bells came naturally. Like I wrote in the liner notes:

There are moments in history when sound becomes more than vibration, when it becomes the very material of memory. Bells have always carried this weight. They call us to gather, they mark time, they echo joy, they toll grief. But they also have a darker lineage. Across Europe, in both the First and Second World Wars, bells were silenced not by time but by fire. They were torn from towers and melted into weapons, their resonant voices recast as artillery. That transformation—from harmony to violence, from resonance to rupture—still lingers in the collective imagination.

The idea to make Battles & Silences a reversal of that story came from Fedor [Teunisse]. At its center is a bell unlike any other: forty-five kilograms of resonant metal, forged not from ore mined in silence but from brass that once screamed across battlefields. Its material began life as Ukrainian bullet casings, smelted in Kyiv in the spring of 2024, gathered in small bars of brass before making their way, under difficult circumstances, to the Netherlands. From there they traveled to the Royal Eijsbouts Bell Foundry in Asten, the same foundry where church bells for cathedrals across Europe have been cast for centuries.

Tell me more about HIIIT. What’s your connection with that group and what role did they play in bringing Battles & Silences to life?

AF: A couple of years ago, I did a project with HIIIT around Philip Glass, where I composed my own music and arranged some Glass pieces for percussion ensemble. That resulted in a CD Vitreous Body that was released by Glass’s own label Blue Mountain. Artistic director Fedor Teunisse wanted to work with me again, but then with Poulson Sq. So that’s where we started to talk about this new project around the sound of bells.

When the idea took the shape of Battles & Silences, Mathijs and I wanted to work with percussionists that would be happy to get into the making and experimenting process with us. We didn’t want to present a score the way a normal ‘classical’ composer would do, but we wanted to develop the sound world and form together with them. Fedor came up with João Brito and Dirge Seçil Kuran, two young percussionists who are both brilliant and prepared to think out of the box. From moment one they were completely with us on this idea. They were very valuable in the process, as they were able to translate our processed tape loops to their instruments. It was amazing to work with these fantastic musicians.

The title of this project seems to be reflected well in the music–there are the “battles” represented by the various segments of sometimes quite jarring and chaotic noise, then the literal “silences” between them. Tell me more about this overall composition of the project and your thoughts on the value of silence within musical pieces.

ML: After initially grappling with the fundamental question of how we, as composers, should engage with this instrument and all that it symbolizes, it quickly became clear that we wanted the bell to be ever-present without actually playing it. The delayed ringing of the bell intensifies its final impact. And what we also noticed during our workshops with the musicians: once it had been struck, it also seemed as if the bell could no longer be removed from the ensemble. The instrument is too heavy to use briefly for a sound experiment and then move on from the bell musically. It was like a kind of black hole. I think eventually this dictated the form of the piece: we processed the instrument in dozens (hundreds?) of ways to completely peel it in sound, with the physical characteristics of the bell in relation to our tape instrument being central. This process ultimately led to the playing of that one pure sound of the bell. In a sense, this process also felt like a genealogy of the material itself, in which beauty, violence and silence are all present.

Written in the booklet for the album is the following passage:

At the core of Battles & Silences is a paradox: that sound can both remember destruction and generate beauty, that silence can be both a wound and a healing. This paradox is not resolved but sustained. The music does not offer consolation through closure, but consolation through resonance.

Can you expand on the meaning of this paradox?

AF: The paradox at the core of Battles & Silences – that sound can remember destruction and generate beauty, and that silence can be both a wound and a healing—reflects the complex, unresolved nature of trauma and memory. Rather than offering closure or a neat resolution, the music sustains this tension, allowing the listener to inhabit a space where loss and beauty coexist. The album does not try to erase or simplify pain; instead, it finds consolation in resonance—the shared experience of sound as a carrier of memory and emotion.

This means that silence is not simply emptiness but an active presence that wounds by its absence and heals by offering space for reflection. Similarly, sound can echo the violence and destruction it recalls but also create moments of unexpected grace and connection. This sustained paradox invites listeners to confront difficult realities without driving to closure, instead fostering a contemplative environment where sound and silence together shape an emotional and ethical engagement with history and loss.

This approach aligns with the project’s broader aim: to resist the idea of neat endings or easy consolation in times of conflict and uncertainty, offering instead a form of empathy and solidarity through attentive listening and shared resonance.

Do you have a favorite track on the album, and, if so, why?

AF: That’s a hard one to answer. For me the second track, Soft Explosions, is probably my favorite. Although, when I say this, I could also have mentioned any other track on the album. We worked intensively with the sound of the bell and its derivatives and disintegration via tape loops. Soft Explosions is the result of bell sound on half speed reel-to-reel tape loop, going through a filter with a tipping point. We turned these tippings manually, which gives the sound an organic feel, but also ominous, as if you are listening to the ghost of that bell. The conversation of that loop with the percussionists and their instruments made it a movement of eerie beauty. But then again, I could tell a similar story about all the tracks on the album.

ML: The piece Stone Rain is important to me. During the process of writing this music, it was the first piece in which content and form came together in a way that felt right to me. The creative process was far from easy; I wondered more often than ever whether we were the right people for this project. After all, why would two composers from the safety of the Netherlands be able to write a piece about a war that is so incredibly real? Don’t get me wrong: by the time this piece was created, we had already made, recorded and researched many beautiful things—the instrument, the bell, sounds fantastic. But it did not transcend the “flat” beauty of that instrument. At a certain point, we analyzed to the bone what we could say with this instrument, and where it touches our reality, where the universal can be found and how this connects to the origin of this instrument. The answer turned out to be right in front of us: the material itself. Just as the bell is made of metal, so is the material we work with—tape. And just as metal can be shaped into an instrument, so too can sound be shaped into something new. Based on that realization, we came up with the idea of not focusing on the primary sound of the bell, but rather paying attention to the background noises, the periphery of the recordings on magnetic tape. This created totally new textures, pulses and patterns that had a life of their own. We used these ‘peripheral sounds’ as basic material for Dirge and João to play. As such a loop of transformation formed itself, from acoustic bell sounds to magnetic tape, to musicians, and through performance as an ensemble with the bell, back to the bell itself. This change in focus (from writing for the bell, to a process-based compositional practice with the bell) came about in the creation of this specific chapter and proved to be the key to the rest of the piece.

Ambient music has often been described as both background and foreground—music that can shape a space while you focus on something else or be listened to with deep intent. Where do you see Battles & Silences on that spectrum?

AF: The performance of Battles & Silences lies somewhere between a concert and an installation. It’s designed to engage listeners not just through music alone but by interacting with the space itself, making the environment an integral part of the experience. The music shapes the acoustic and emotional atmosphere, inviting both focused listening and moments where sound becomes part of the ambient environment around the audience. The venue and its characteristics are crucial in how the sound unfolds and resonates, making the spatial aspect inseparable from the music’s impact. In that way, Battles & Silences creates a shared sonic space that honors silence, tension, and transformation simultaneously, allowing listeners to inhabit a dynamic and contemplative sound world. That being said, the general feedback of the audience was that Battles & Silences is an intense and sometimes overwhelming experience.

Production Notes

Can you tell me more about how you recorded and processed the sounds of the bell for this record? I’m aware you used analog tape–can you describe how the sound evolved?

ML: My whole artistic practice is based around the use of analog instruments. There are a lot of different reasons for this, but one of the main reasons for me to work exclusively analog is the fact that these instruments have a will of their own. They’re not hiding their physicality (you could also say ‘they are not perfect’). This turned out to be one of the key elements when we were searching for the connection between our aesthetics and the origin of the bell.

AF: I agree. The notion of ‘imperfection’ and ‘physicality’ as a sound quality is a really important aspect of our duo. It also asks for a way of working ‘inside time’, whereas working with a computer could evolve outside time, because of the visual and plastic way sounds present themselves in the UI. Working with tape and analog instruments requires a form of listening and interacting that very much takes place in the moment and is final. Like a painter working on a canvas.

Were there any other specific pieces of gear that inspired or played a major role in the creation of Battles & Silences? How did you decide on the electronics you wanted to pair with the bell?

ML: My good old Korg Stage Echo SE500 is an important piece of gear on this record. This device’s sound-on-sound function is a particularly often used option on this record. This is because the decay of the recorded material can be controlled relatively well (see the Basinski reference that Anthony mentioned earlier, for example). I have also modified the Korg so that it is possible to transpose the material on the tape loop in fixed intervals, chromatically for almost 1.5 octaves. This can clearly be heard in the “Voices” chapter. The voices of Brito and Kuran merge, decay and transpose in a way that can only be achieved with this machine, and it is so reliable that it can also be used live.

AF: I come from a contemporary classical background, more or less. In electronic music, I like to work with instruments instead of a laptop. I want to have the tactility, the performative aspect and the ‘analog’ way of working. For this project I mainly used Elektron’s Octatrack and Digitakt—the Octatrack being a mixture between a sampler, synth, modular system, mixer, and tracker. And the Digitakt used as a synth and generative system. In Mathijs’s studio, we worked a lot with reel-to-reel tape loops, analog measuring gear (filters, etc.) and his plus-sized mixing board.

Do you have a favorite piece of gear to which you’ve found yourself returning frequently, no matter the project?

ML: Not necessarily a piece of gear (if you exclude tape as an instrument—tape is always around, and I’m always transposing recorded material to create dialogues of different voices coming from one source), but I do have an ever-returning method when writing and/or producing music: the use of feedback. Sonically speaking, Battles & Silences is full of acoustic and electronic feedback. I am drawn to the poetic nature of the phenomenon (acoustic feedback can be understood as a system which gives a voice to your environment, and on the other hand electronic feedback can be seen as an auto-poetic system: the electronic circuit sounds itself, it demonstrates what its circuits are doing through sound), as well as its musical versatility and dynamic range. So when feedback is understood as a means of connecting the various elements present in a creative process and allowing them to sound together as one common voice, it is more than just a method for achieving a certain sound. It is a means of bringing to the fore the sum total of all the elements that are part of the creative process (i.e. from instruments to musicians and location).

AF: For me, it depends on the project and music that I intend to make. I am very fond of my Buchla Music Easel, the most punky synth I own. And I also like my Lyra-8 by SOMA. Both have a character and and serendipity factor that is joyful to work with. My go-to instrument would be the Octatrack, because of its versatility and portability, or the Digitakt, for the same reason.

As a duo, how do you tend to collaborate with each other? Any specific system or method, or is it relatively freeform? Live in a room together or remote?

ML: We work relatively freeform, but if I would have to name one thing it would be the method of staying with the trouble (Donna Haraway). I think we are good at tending to material for a long period of time. Giving it time to unfold itself. We are not too radical in the post productional phase, much of the work is done while we are working with the material, as opposed to working on the material. For me this is a very specific part of our collaborations. In a very practical sense we record almost everything in my analog studio, where we are both present. Mixing and technical preparations for digital release is done by Anthony in his studio.

Is there anything else you'd like to share about your production and/or creative process that other artists might be interested to know? Any other hardware, software, techniques, rituals?

ML: Be aware of your interface (any interface, from piano, to recorder, whatever) . It makes choices for you. Which isn’t a bad thing, but I think it is good to be aware of this ‘second composer’ at the desk when you are doing your musical work.

AF: I agree with Mathijs. This ‘second composer’ can be a strength if it brings you surprises and happy accidents—but it can also be a pitfall if it forces you to compose in a certain way. That’s why I only have a few synths and pieces of gear that I like to work with—mostly the ones that are ‘open’.

Final Thoughts

What’s the best advice you’ve ever been given?

AF: Haha! That would be “steal everything,” an advice given by György Ligeti in one of my conversations with him.

Who or what are your greatest musical inspirations and why?

AF: My greatest musical inspiration must be Morton Feldman. His late works, like For Samuel Beckett, draw me in with their extraordinary sense of time and space – sounds that unfold with microscopic patience, repetition that feels both static and alive, creating a world where every timbre and silence holds equal weight. Feldman’s music taught me to listen to the “skin of sound,” that tactile surface where texture and presence matter more than melody or development, influencing my own approach to composition profoundly.

What fascinates me most is how he bridges music and visual art, identifying more with painters like Rothko and Guston than with traditional composers. This cross-disciplinary thinking resonates with my own projects, where sound becomes an environment rather than a narrative, inviting deep, immersive listening. Feldman’s ability to sustain paradox—beauty in sparseness, intensity in quiet—has shaped everything from my ambient explorations to Battles & Silences.

ML: I’m too fickle to give one definitive name. Over the last few weeks Aaron Dilloway has been very high on my personal inspirational list. I happened to attend one of his performances in Brussels a couple of weeks back, and he completely blew me away. It was the first time I had seen him play live and I was amazed by the degree of control he had within a chaotic world of sound.

What do you think about the current state of the music industry for independent artists and those who create in more niche categories like ambient? How do you approach publishing and selling your work? Any thoughts on the future of the music industry?

AF: The word pair music industry has always made me unhappy. The capitalist idea that music is successful only when it sells goes against my grain. I believe that there is a viable audience for every thinkable niche, and that music is about building communities more than about making money. In the current state of the music industry it’s not the musicians, but publishers, shareholders making money out of the artist. The future of the music industry would be a future without the industry. But I also realize that that is a pipe dream. I think every artist should create the art they want to create, regardless of algorithms. That can be tough at times, but there will always be people who believe in your art.

ML: There is the macro scale of Big Tech Bros which makes me feel helpless and flat out angry. On the other side there is the micro scale of people coming together around sound and sharing fundamental experiences with each other. It may be naive, but I truly believe that togetherness will always prevail over the emptiness of the content machine that has been built up. Of course, there are many caveats, particularly from an economic perspective, and I have no answer to that other than despondency. But I experience those moments—such as at the Dilloway concert—as very fundamental gatherings that cannot be expressed in monetary terms.

Anything else you’d like to share?

AF: I think it’s important that there are zines and blogs like this, that row against the stream, are curious for new sounds and build communities. Music should be precisely that, a network of communities—not a commodity for a few billionaires and their shareholders.

Where is the best place for listeners to find and support your work?

AF: Our music is found on all streaming platforms, but a better place for support is on Bandcamp. We have our personal pages there (AF, ML), but also both our duos Poulson Sq. and LOFAR are represented on Bandcamp. Apart from that, I think that a live concert is ultimately the best place to experience our music.

Battles & Silences is available for purchase on Bandcamp (digital, €9 EUR [$10.52 USD]; Limited Edition CD €12 EUR [$14.03 USD] plus shipping)

Battles & Silences is also available on most streaming services.

That’s all for this conversation—I hope you enjoyed it. Thank you for reading, friend. Until next time.

Your friend,

Melted Form

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Anthony Fiumara and Mathijs Leeuwis for taking the time to answer all my questions in great detail, and to continue shining a spotlight on the horrific war of aggression still happening in Ukraine. Additionally, thank you to all of the folks at HIIIT and everyone else involved with bringing Battles & Silences to life.

Want more great ambient music? Subscribe!

Every Friday, I send out a newsletter with new music recommendations, including a handful of great new ambient records. I prioritize small label and independent artists, but I also share a list of major records I’ll be listening to from other genres like electronic, indie, alternative, jazz, pop, and more. You may even hear some music of my own, too.

Read my latest weekly post:

Read the previous issue of Instrumental Conversations:

Ways to Support My Work

Upgrade to a paid subscription for some extra goodies. Full price is $5/month or $50/year, but I also offer no-questions-asked, pay-what-you-can discounts on the annual subscriptions.

As an alternative to subscriptions, you can buy me a coffee for an easy one-time tip.

Referrals also mean a lot! If you enjoy this newsletter, please consider sharing it with a friend, a family member, a coworker, or your social media followers. The more it grows, the more ears can hear the music shared here.

Join Our Growing Community on Discord

Hum, Buzz, & Hiss has a free Discord server where music fans and artists hang out together, share music, chat about our work, and learn from each other. Plus, you’ll get some behind-the-scenes stuff and even more music recommendations from me. I’d love for you to join us! Click the button below and I’ll see you there.

Afterword—Let’s Get In Touch

Are you an artist, a label owner, or a member of the press? Want to share news of your upcoming release, a sponsored ad, or a guest post for a future Hum, Buzz, & Hiss issue? Email me at: meltedform@gmail.com.

As always, I would love to hear and recommend your music, especially if it’s new and ambient/electronic/experimental. However, please note that I may not be able to respond to every inquiry I receive.